Atlas has tracked nearly $750 million of new estimated investment committed to medium- and heavy-duty (MDHD) charging from the beginning of 2024 through mid-January 2025, reaching a total of more than $30 billion. Of this new investment, the public sector added $530 million, driven largely by the first two rounds of the federal Charging and Fueling Infrastructure (CFI) Discretionary Grant Program, which awarded $377 million for MDHD charging across seven states, as well as the federal Clean School Bus program, which awarded $192 million across 49 states and the District of Columbia. Private investment grew by $211 million, 81 percent of which is from estimated infrastructure investments associated with announced fleet deployments from Amazon, Zeem Solutions, Einride, and Watt EV.[1] This is an update to a data story Atlas released in January 2024. Table 1 shows the increase in estimated investment in MDHD charging infrastructure since the beginning of 2024, broken out by type of investor.

Table 1: Estimated increase in MDHD charging investments since the beginning of 2024 (by date of announcement/commitment)

|

Investor Type |

Through 2023 |

Through January 15, 2025 |

Increase |

|

Public |

$20.28B |

$20.81B |

$0.53B |

|

Private (Non-Utility) |

$4.24B |

$4.45B |

$0.21B |

|

Private (Utility) |

$1.72B |

$1.72B |

$0.00B |

|

Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) |

$3.28B |

$3.28B |

n/a[2] |

|

Total |

$29.51B |

$30.26B |

$0.75B |

Investments in MDHD charging are not just being announced, they are being deployed, and a growing number of large MDHD charging sites are being planned, built, and placed into service. In the first data story, Atlas tracked 39 operational or planned large charging sites specifically meant for MDHD vehicles.[3] Since the beginning of 2024, that number has grown to 44 sites, representing more than 1,600 DCFC ports. Many private fleets do not disclose their charging plans, so this number is just a sample, not a complete total. Many of these new sites are very large in terms of number of ports and their power level, with one operational site reaching 96 direct-current fact charging (DCFC) ports. Table 2 lists planned, under construction, and operational sites and their port counts and power levels. See Atlas’s first data story or Atlas’s MDHD Charging Investments Dashboard for a list of all the other MDHD charging sites Atlas has tracked so far.

Table 2: Sample of MDHD charging sites that were planned, began construction, or became operational in 2024

|

Company |

City |

State |

Status |

Number of DCFC Ports |

Number of Megawatt Charging System (MCS) Ports |

|

Prologis |

Los Angeles |

CA |

Operational |

96 |

0 |

|

Zeem Solutions |

Los Angeles |

CA |

Under construction |

84 |

0 |

|

Watt EV |

Bakersfield |

CA |

Operational |

31 |

3 |

|

Watt EV |

San Bernardino |

CA |

Operational |

24 |

0 |

|

Watt EV |

Gardena |

CA |

Operational |

18 |

0 |

|

New York Metropolitan Transit Authority |

Queens |

NY |

Operational |

17 |

0 |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Ontario |

CA |

Planned |

4 |

1 |

|

Watt EV |

Seattle |

WA |

Planned |

unknown |

unknown |

Several of these new sites are demonstrating technological advances and innovative business models that could help facilitate more rapid electrification of MDHD vehicles. For example, two of these new sites include Megawatt Charging System (MCS) chargers, which are capable of charging a vehicle at a power level of one megawatt or greater. These fast charging speeds are particularly important for MDHD vehicles, since reducing downtime is essential for commercial fleets’ business models. MCS ports also have enhanced reliability requirements, making them especially well-suited for commercial fleets that cannot tolerate risk associated with unreliable charging infrastructure. One operational site in Bakersfield, California, includes three MCS ports. The charging provider of that site, WattEV, has stated that all future depots they build for MDHD charging will include MCS chargers.

Several of these planned and operational sites are also demonstrating innovative business models that other sites could follow to help support MDHD electrification. For example, while many MDHD fleets build their own private charging depots, some recent sites are open to the public, allowing any truck to charge for a fee. This could help MDHD fleets begin to electrify without having to make large investments in charging infrastructure, at least not right away. Box 1 describes three sites that have MCS ports and are publicly accessible.

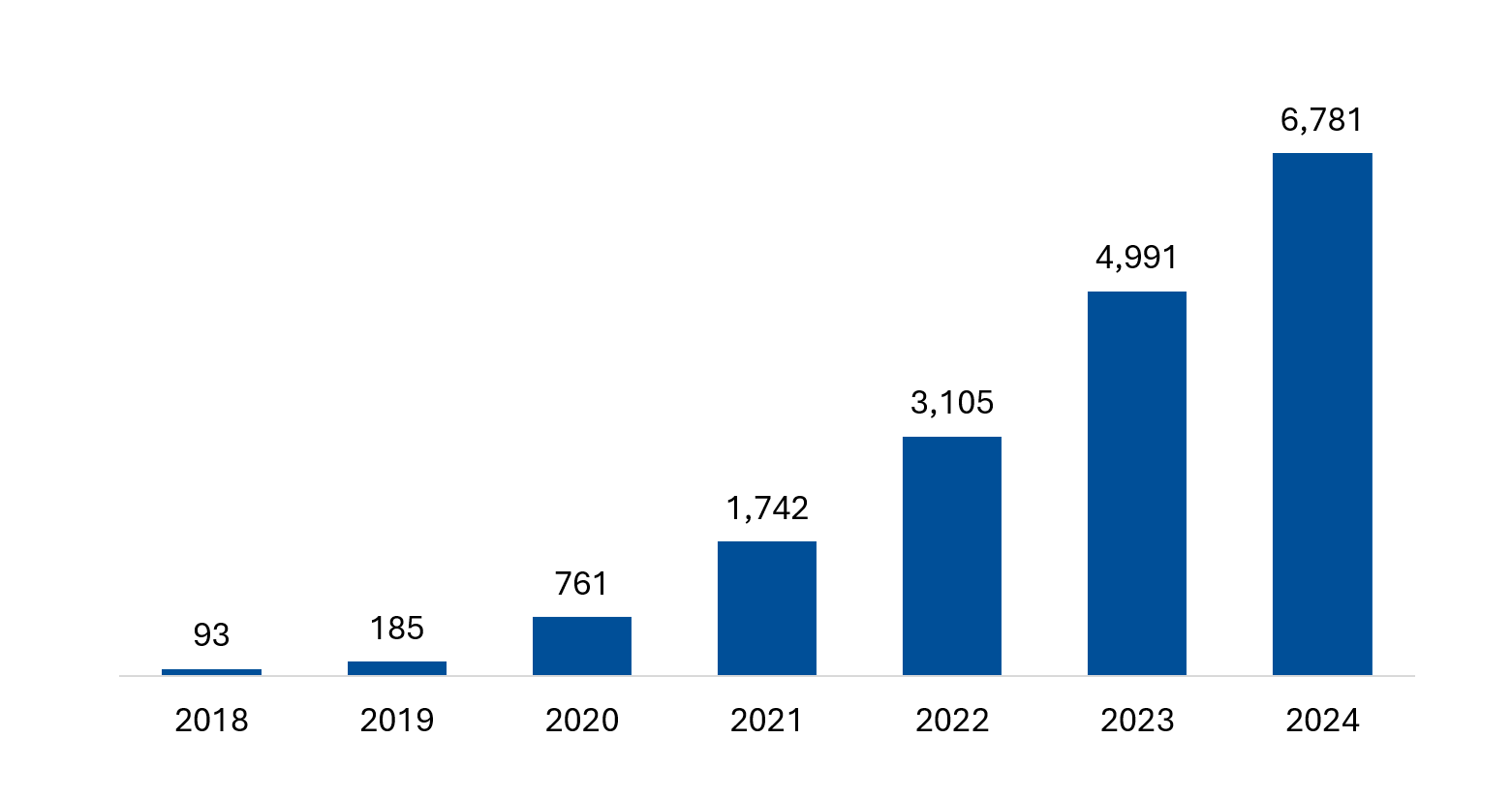

In the first data story, Atlas analyzed data from the Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC) to identify charging sites that are well-suited[4] for MDHD charging. Atlas updated that analysis and found that the number of DCFC ports that are well-suited for MDHD charging has increased consistently each year. Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of DCFC ports that are well-suited for MDHD charging.

Figure 1: Cumulative DCFC ports at stations well-suited for MDHD charging (from AFDC) by date open

See methods section for more information on how Atlas used data from AFDC to estimate the number of sites that are “well-suited” for MDHD charging.

Source: Alternative Fuels Data Center

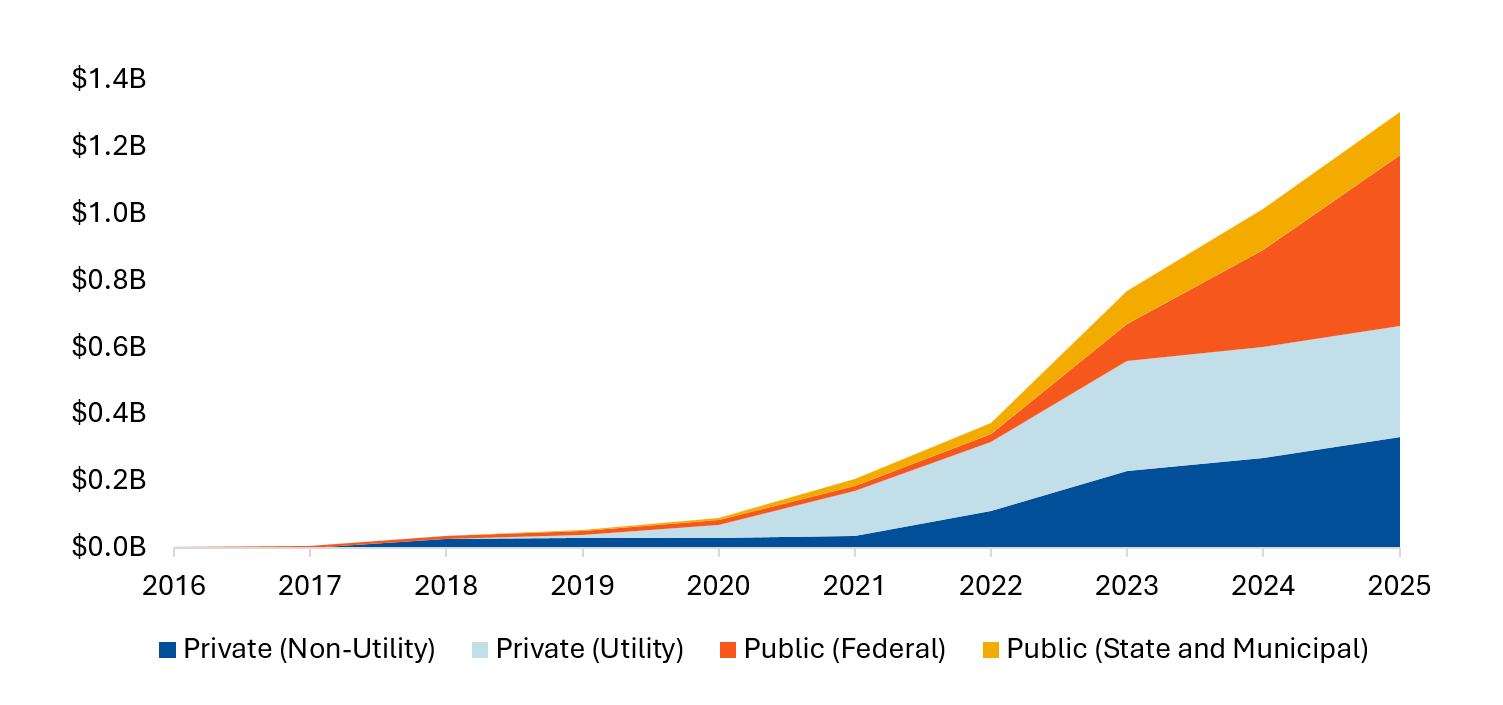

An additional sign of growing momentum in MDHD charging investment in the United States is the significant increase in investments in MDHD charging infrastructure beyond California. The Golden State has long been a leader in transportation electrification across vehicle classes and particularly in MDHD electrification. While California still leads, activity in other states shows that MDHD electrification is happening in a meaningful way elsewhere. Figure 2 shows cumulative estimated investment in MDHD charging by investment type outside of California.

Figure 2: Estimated cumulative non-California investment in MDHD charging (by date of announcement/commitment), as of January 15, 2025

The continued growth in estimated MDHD charging investment and the growing number of planned and operational MDHD charging sites that include large numbers of high-power chargers indicates that there is momentum in MDHD electrification in the United States.

Methods

LCFS & 30C Tax Credit

The estimated Low Carbon Fuel Standard value is based on modeling from Dean Taylor Consulting for California, Oregon, and Washington and does not include capacity credits. It uses a 2023 – 2032 EV adoption trajectory for those three states that meets President Biden’s light-duty vehicle goal of 50 percent zero-emission vehicle sales share by 2030 (which is lower than the trajectory modeled in the EPA’s proposed vehicle emission standards), an MDHD EV adoption curve modeled on the EPA’s proposed emissions regulations for medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicles, and modeling from Atlas’s INSITE tool of MWh demanded by MDHD vehicles.

The estimated 30C tax credit value is based on modeling from Atlas Public Policy, based on EV adoption consistent with a) 50 percent of light-duty vehicle sales being battery electric by 2030 (in line with President Biden’s goal), and b) medium- and heavy-duty battery electric vehicle adoption consistent with the EPA’s proposed light-duty and medium-duty vehicle and heavy-duty vehicle regulation. Atlas assumes that 1) all qualifying projects receive the tax credit and, 2) on average, qualifying projects will receive tax credits worth 18 percent of covered costs. Atlas used the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s official list of qualifying census tracts to determine which projected charging infrastructure installations will qualify for the tax credit.

Private Funding

Private funding in this analysis includes public commitments from private companies to invest in EV charging infrastructure dedicated for medium- and heavy-duty vehicles. This analysis conservatively excludes funding commitments that could go to light-duty vehicles, if it is not clear how much is expected to go to MDHD vehicles. This also includes estimated charging infrastructure investment associated with commitments from fleets to deploy electric vehicles. Investment is calculated based on the estimated charging infrastructure needed to support the number of EVs committed by fleets.

Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC)

AFDC identifies charging sites as capable of supporting MDHD vehicles based on whether MDHD vehicles could physically fit in the charging parking spaces (e.g., the spots are pull-through spots). Importantly, AFDC only collects this data for sites where it does not have access to a web application programming interface (API). To try to fill in some of this gap, Atlas identified certain site types that generally provide services to MDHD vehicles, such as truck stops, and added those sites to the count of sites that are well-suited to support MDHD charging. These chargers are not included in the investment total ($30 billion), but are simply discussed in the report.

Public Funding

This analysis includes the following:

- Public funding awarded directly to MDHD charging.

- For public funding awarded to MDHD vehicles, Atlas includes the estimated investment in charging infrastructure needed to support the funded vehicles.

Funding that has not yet been awarded but that might go toward MDHD charging is not included in this analysis.

Utility Filings

This analysis includes approved investor-owned utility funding for which MDHD charging is eligible. Therefore, some of the utility funding included will likely not go toward MDHD charging. However, the analysis conservatively only includes the specific sub-programs for which MDHD charging is eligible. For example, if a $1 million program is approved that includes a residential sub-program and an MDHD sub-program, only the funding associated with the MDHD sub-program is included. This analysis also conservatively only includes funding directly associated with charging infrastructure investment. In other words, administrative budgets or education budgets are not included.

Avoid Double Counting

Investment associated with deployed private fleets in California is excluded from the private funding count because it is assumed that all MDHD vehicles deployed in California received funding from the Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus (HVIP) program, which is already counted under public funding. This is likely a very conservative assumption since many private fleets receiving HVIP funding will also contribute their own funding. Similarly, investment associated with deployed transit and school bus fleets is excluded from the public funding count because it is assumed that these fleets used funds from public programs that are already counted under that category. Similarly, this is likely a very conservative assumption since many of these fleets likely contributed their own funds as well. Finally, to be conservative, investment associated with specific fleets is reduced to 70 percent, to avoid double counting public and/or utility funding the fleets use.

- See the Methods section for details about how Atlas estimates charging infrastructure investment associated with announced vehicle deployments.

- Atlas tracks estimated investment by the date the investment was announced or committed. Therefore, estimated investment from the LCFS program is tracked in the year the program was announced and will not change.

- This analysis considers “large” MDHD charging sites to be those with at least five direct current fast charging (DCFC) ports specifically meant for MDHD vehicles.

- Sites are considered “well-suited” if they have been identified by AFDC as MDHD charging sites or they are located at site types that generally provide services to MDHD vehicles, such as truck stops. See the Methods section for more details about how sites are determined to be well-suited for MDHD charging from AFDC data.