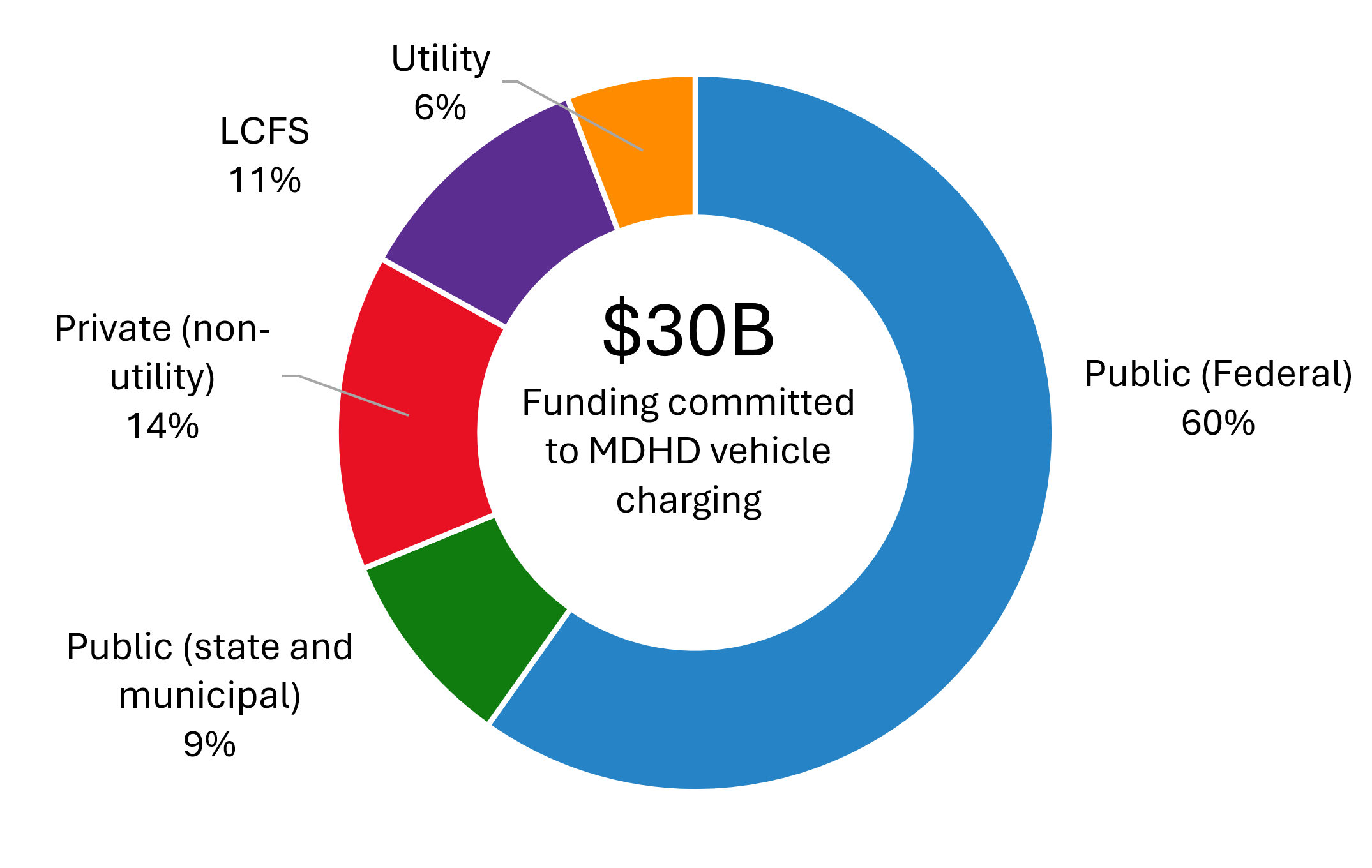

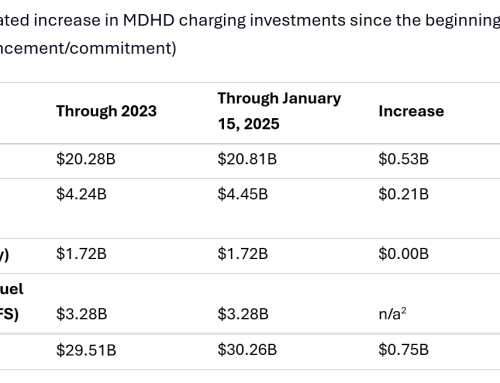

The public and private sector are making transformative investments in medium- and heavy-duty (MDHD) electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure throughout the United States. An estimated $30 billion is going toward supporting MDHD charging across federal, state, and local governments, in addition to investor-owned utilities and the private sector.[1] Major private companies are demonstrating that they are capable of and serious about making electric MDHD vehicles a key feature of their operations, with companies like Amazon, Daimler, Anheuser-Bush, Sysco, and United Parcel Service (UPS) already operating MDHD charging facilities for their fleets. Many other fleets are making similar moves, and a search through press releases and news articles identified at least 39 large MDHD charging sites with at least five direct current fast charging (DCFC) ports—some with as many as 120 DCFC ports—either planned, in construction, or operational. Furthermore, at least 4,800 operational DCFC ports across 600 sites are well-suited to support MDHD charging, based on an analysis of data from the Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC). This initial progress and the substantial planned investment demonstrates that the United States is actively preparing for widespread MDHD electrification.

This analysis is a multi-data source effort to quantify the total investment committed to MDHD charging in the United States, as well as begin to assess progress toward deployment. The analysis is unique in the comprehensiveness of the data sources included, from large databases to targeted review of company press releases, electric utility filings, public funding program documents, news articles, and modelling efforts.

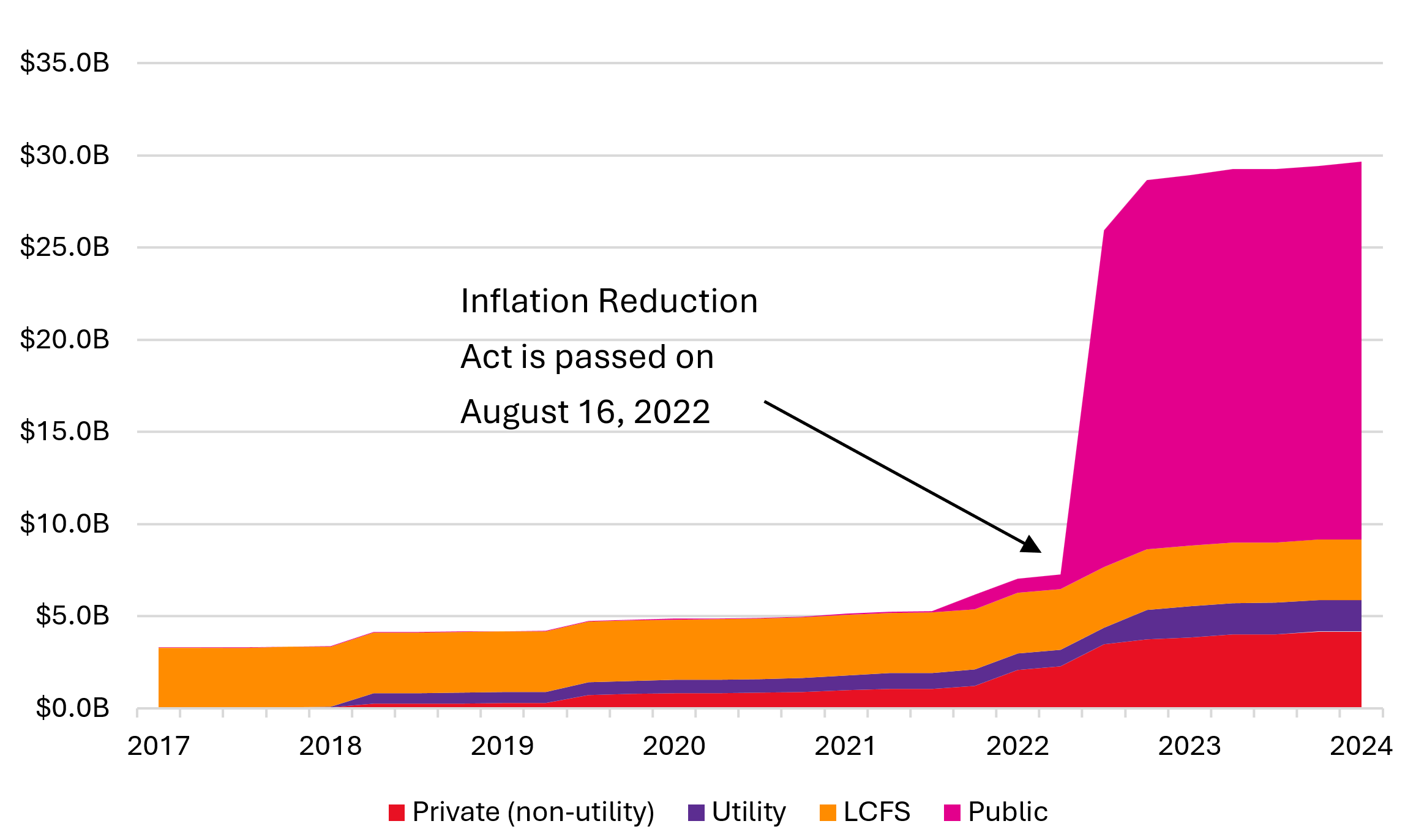

Figure 1: Estimated cumulative investments in MDHD charging by announcement date as of December 2023

Public funding amounting to approximately $21 billion accounts for the greatest portion of the $30 billion of planned MDHD investment. This $21 billion is driven largely by the 2022 federal Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides renewed funding for key programs such as the Low- or No-Emission Grant Program, the Clean School Bus Program, the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act, and several others.[2] This unprecedented level of funding has the potential to accelerate domestic progress towards widescale electrification of MDHD vehicles. Notably, while this $21 billion includes an estimate of 26 U.S. Code § 30C tax credit payments, to be conservative, it does not include the estimated underlying investments that would result in these tax credit payments.[3] There is also a substantial amount of funding that has not yet been awarded but that may go toward MDHD projects. This funding is not included in the $21 billion estimate but is included in Table 4 in Appendix A, which lists at least $306 billion of funding that has gone or could go toward MDHD projects. Therefore, the true level of public funding for MDHD charging is likely higher than $21 billion.

In addition to federal funding, states and municipalities are providing a meaningful amount of funding for MDHD charging. The vast majority to date is from California, with $2.4 billion out of $2.6 billion from the California Energy Commission. So far, Florida and Oregon are the only other states providing more than $10 million of funding for MDHD vehicles. Oregon’s Zero-Emission Fueling Infrastructure grant program is funded with $15 million and Florida is deploying an estimated $15.6 million in charging infrastructure to power 445 school and transit buses funded by the state’s Volkswagen (VW) settlement program. Figure 2 below shows total funding available for MDHD charging, with federal and state funding broken out separately.

FIGURE 2: ESTIMATED U.S. MDHD CHARGING INVESTMENTS AVAILABLE THROUGH NOVEMBER 2023

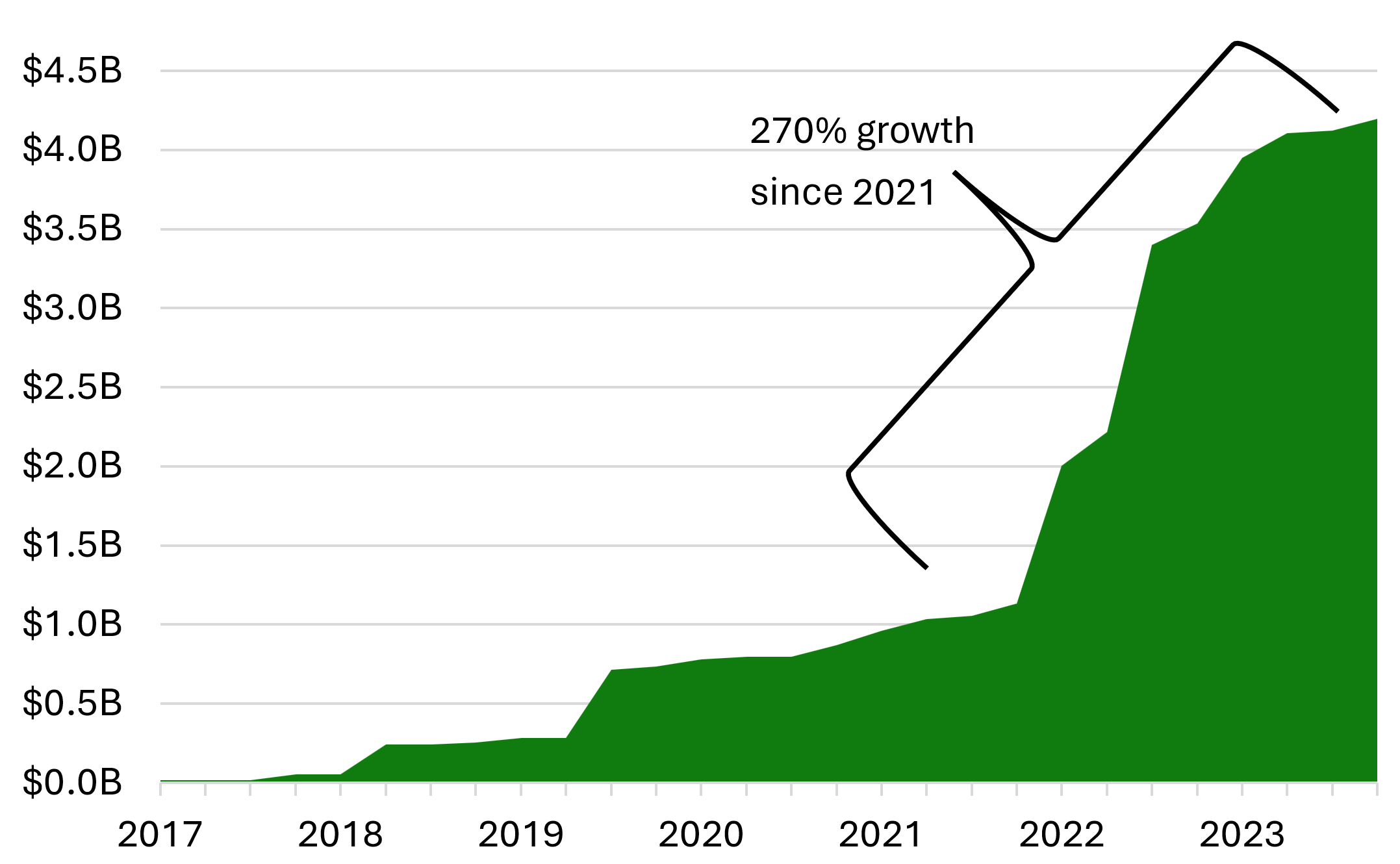

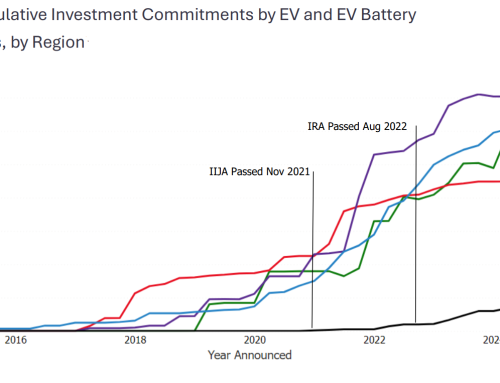

The private sector (not including investor-owned utilities) is also significantly ramping up its investment plans for MDHD charging, with $4.2 billion in planned investments through 2023. This represents almost triple what had been planned through 2021 and includes company announcements and investments in charging associated with public and private fleet deployments and plans.[4] Figure 3 shows this 270 percent growth in private funding for MDHD charging in just two years.

Figure 3: Estimated cumulative private sector (non-utility) investments for MDHD charging

While the greatest portion of private sector investment commitments are for investments in California, other states are catching up, and private company investment commitments outside of California more than tripled from $105 million in 2021 to $322 million through 2023. Table 1 lists the top ten private fleets by planned MDHD charging investment. Notably, at least six of these private fleets have already broken ground or have begun operating MDHD charging sites.

Table 1: Top Ten Private Fleets Investing in MDHD Charging

|

Investor |

Investment |

Status[5] |

|

TeraWatt Infrastructure |

$1,000,000,000 |

Under construction site(s) |

|

Daimler AG |

$650,000,000 |

Operational site(s) |

|

Amazon |

$520,532,376 |

Operational site(s) |

|

Anheuser-Busch Cos. |

$194,313,280 |

Operational site(s) |

|

Sysco and Operating Companies |

$174,272,000 |

Operational site(s) |

|

Merchants Fleet |

$130,384,019 |

not available |

|

Werner Enterprises |

$108,920,000 |

not available |

|

Pride Group Enterprises |

$75,228,108 |

not available |

|

UPS Inc. |

$68,426,848 |

Operational site(s) |

|

Ryder Systems, INC. |

$68,079,321 |

not available |

At least 278 fleets have made investment commitments to electrify MDHD vehicles.[6] This includes 81 state and municipal fleets and 197 private fleets, including Amazon, Anheuser-Busch, and Sysco. Table 2 shows which vehicle classes are being electrified in these fleets. While class 2b cargo vans have a significant lead, class 7 and 8 vehicle electrification commitments grew by more than 250 percent from 2021 to 2023.

Table 2: Fleet Electrification Plans by Vehicle Class (public and private fleets)

|

Fleet vehicle class |

Fleet EVs planned |

|

Class 2b (cargo vans) |

168,012 |

|

Class 3 |

15,157 |

|

Class 8 |

5,992 |

|

Class 5 |

5,450 |

|

Class 4 |

3,791 |

|

Class 6 |

663 |

|

Class 7 |

525 |

|

Unknown |

21 |

|

Grand Total |

199,611 |

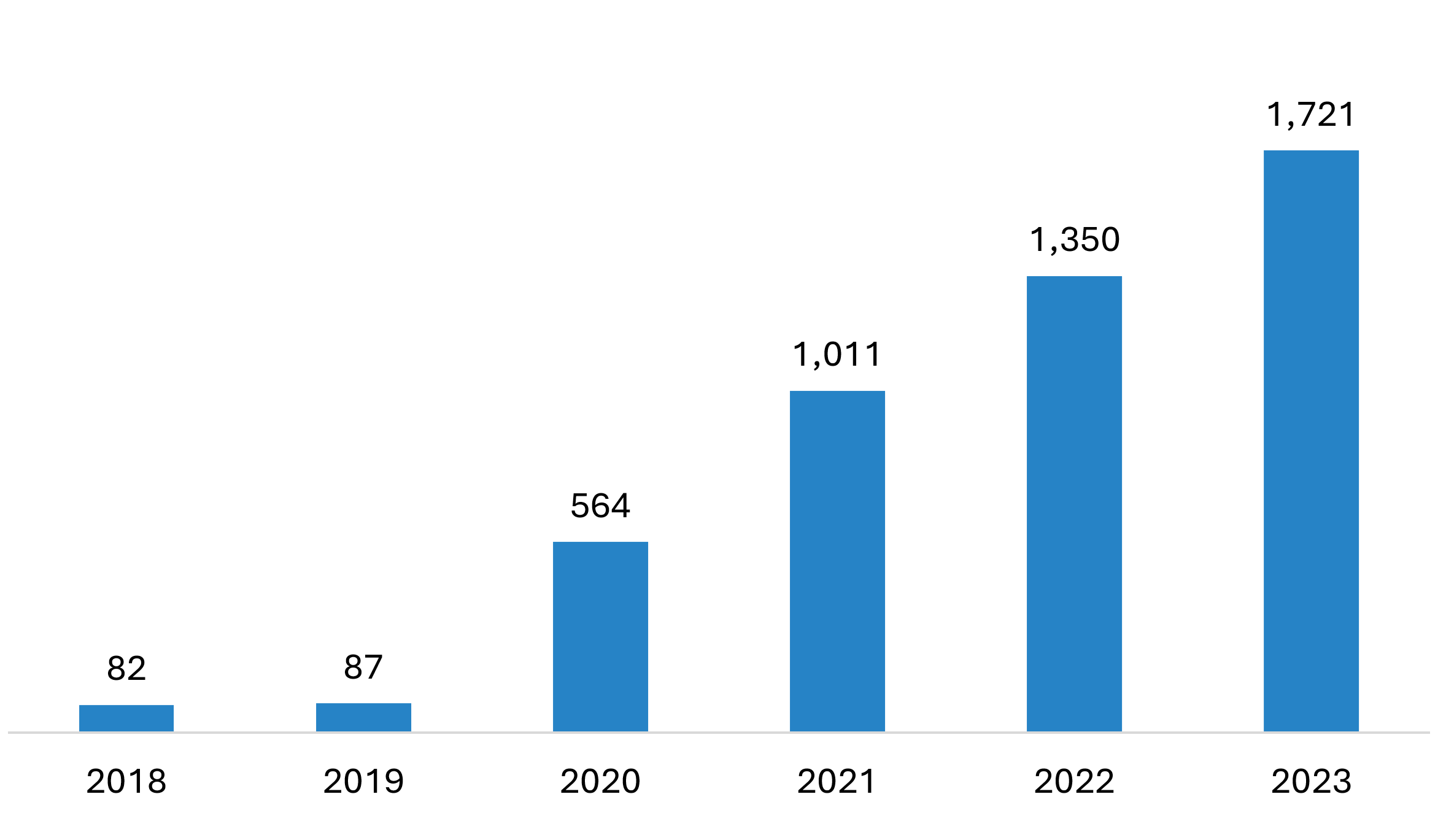

Analysis of data from the AFDC identified at least 4,800 DCFC ports across 600 charging sites that are well-suited for MDHD charging.[7] This number has increased consistently in recent years, growing by 70 percent since 2021 (see Figure 4). These sites are geographically spread out with Texas and Florida taking the top two positions, ahead of California, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 4: DCFC ports at sites well-suited for MDHD charging by year (from AFDC data)

TABLE 3: DCFC PORTS AT SITES WELL-SUITED FOR MDHD CHARGING BY STATE (FROM AFDC DATA)

|

State |

DCFC Ports |

|

Texas |

664 |

|

Florida |

546 |

|

California |

443 |

|

Pennsylvania |

384 |

|

Virginia |

340 |

|

Other |

2,450 |

|

Total |

4,827 |

Beyond data from AFDC, a search through press releases and news articles found at least 39 charging sites with five or more DCFC ports specifically meant for MDHD vehicles that are either planned, in construction, or operational. Importantly, many private fleets do not publicly announce plans for building MDHD charging sites, and therefore there are likely many more sites than these. Table 5 in Appendix A lists these sites and Box 1 below describes several in more detail.

Electric utilities are also providing funding to MDHD charging through rebates or direct investment in chargers and the utility infrastructure needed to power them. In total, $1.7 billion of approved investor-owned utility funding could support MDHD charging, nearly double the amount that had been approved through 2021. Notably, some programs make funding available to light-duty vehicle charging as well and do not specify how much will support light-duty versus MDHD charging. However, some investor-owned utilities (IOUs) programs specifically focus on MDHD charging. California leads in such programs, with all three major IOUs offering funding targeting electric trucks or buses. Outside of California, at least 15 non-California IOUs offer programs with charging targets specifically for MDHD chargers.[8] Specific funding programs such as the programs described here, are not the only way utilities are supporting MDHD charging. In fact, many utilities are making plans to upgrade the distribution system to support higher volumes of MDHD vehicles. These types of investments are typically reviewed by state regulatory commissions and utilities may often earn a return on them.

Low Carbon Fuel Standard programs in California, Washington, and Oregon are also providing substantial funding. At $3.3 billion, these programs make up 11 percent of total funding available to MDHD charging. With only three states contributing this substantial amount of funding, the impact that adoption of similar programs in other states could have is notable.

Looking forward, a recent analysis by Atlas Public Policy finds that the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) formula program, while mainly focused on light-duty chargers, is being implemented in a way that could support MDHD charging. Specifically, Atlas reviewed 159 awarded NEVI sites across seven states and found that 98 of those sites are large gas stations or rest stops that can or already do accommodate large pull-through parking spaces for MDHD vehicles and therefore they may potentially host MDHD charging sites in their initial rollouts or in future expansions.

The public and private sector have made transformative levels of investment available to support MDHD charging in the United States. The $30 billion included in this analysis is conservative in a number of ways, including its exclusion of private and public investments that will likely take advantage of the tax credits in the IRA, as well as the exclusion of public funding programs for which MDHD charging is eligible but is not the target. The already demonstrated willingness and capability of fleets to build large MDHD charging sites as well as the steep rate of growth in planned investments from public and private entities indicates that the United States is well-positioned to provide the charging infrastructure necessary to achieve broad electrification of MDHD vehicles.

APPENDIX A

Table 4: Federal funding for which MDHD charging is not the focus but is eligible

|

Program |

Investment (billions) |

|

National Highway Performance Program |

$148.0 |

|

Surface Transportation Block Grant Program |

$72.0 |

|

Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement program |

$13.2 |

|

Infrastructure for Rebuilding America Grant Program |

$8.0 |

|

Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity |

$7.5 |

|

National Highway Freight Program |

$7.2 |

|

Carbon Reduction Program |

$6.4 |

|

Low or No Emission Vehicle Program |

$5.6 |

|

Federal Lands and Tribal Transportation Program |

$5.2 |

|

Bus and Bus Facilities Grant Program |

$5.1 |

|

National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program |

$5.0 |

|

Clean School Bus Program |

$5.0 |

|

Climate Pollution Reduction Grants |

$5.0 |

|

Clean Ports Program |

$3.0 |

|

Grants for Charging and Fueling Infrastructure |

$2.5 |

|

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

$2.3 |

|

Rural Surface Transportation Grant Program |

$2.0 |

|

United States Postal Service Clean Fleets |

$1.7 |

|

Clean Heavy Duty Vehicle Program |

$1.0 |

|

State Energy Program |

$0.5 |

|

Grants for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Improvements at Public School Facilities |

$0.3 |

|

Total |

$ 306.5 |

Table 5: Sample of MDHD Charging Sites with Five or More DCFC Ports

|

Company/ Organization |

City |

State |

Status |

Number of Ports |

Description |

|

Forum Mobility |

Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez |

CA |

Planned |

120 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. This is one of three planned sites in Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez. |

|

Forum Mobility |

Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez |

CA |

Planned |

120 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. This is one of three planned sites in Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez. |

|

Forum Mobility |

Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez |

CA |

Planned |

112 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. This is one of three planned sites in Unincorporated Rancho Dominguez. |

|

Forum Mobility |

Livermore |

CA |

Planned |

96 |

Forum Mobility 96-truck charging depot to serve trucks driving between Port of Oakland and Central Valley |

|

One Energy |

Findlay |

OH |

Under Construction |

90 |

One Energy Megawatt Hub |

|

Watt EV |

Sacramento |

CA |

Planned |

90 |

Sacramento County WattEV Innovation Freight Terminal (SWIFT) – DCFC |

|

Forum Mobility |

City of Vernon |

CA |

Planned |

80 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. |

|

Forum Mobility |

City of Fontana |

CA |

Planned |

64 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. |

|

Forum Mobility |

City of Compton |

CA |

Planned |

52 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. |

|

Forum Mobility |

City of Long Beach |

CA |

Planned |

48 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. |

|

Schneider |

El Monte |

CA |

Operational |

32 |

16 dispensers with dual cables supporting up to 350 kW each. Schneider is transitioning the heavy-duty tractors at its South El Monte, CA site to battery electric vehicles. When the transition is complete, all 92 trucks at the site will be electric and will operate in domestic intermodal applications that are primarily short haul. |

|

Sysco |

Riverside |

CA |

Planned/ Operational |

29 (planned) 11 (Operational) |

Sysco Riverside facility – 40 class-8 vehicles, 40 DCFC (29 not yet built DCFC) |

|

Watt EV |

Long Beach |

CA |

Operational |

26 |

WattEV Port of Long Beach 26-port Charging Depot |

|

Forum Mobility |

City of Oakland |

CA |

Planned |

24 |

One of the first nine sites Forum Mobility has identified in Northern and Southern California to electrify MDHD vehicles servicing the Port of Long Beach and the Port of Oakland. |

|

Terawatt Infrastructure |

Rancho Dominguez |

CA |

Under construction |

20 |

TeraWatt Infrastructure 7 MW truck charging sites in Rancho Dominguez, CA , for Port of Long Beach Trucking Operations |

|

Reyes Coca-Cola Bottling |

Downey |

CA |

Operational |

20 |

Reyes Coca-Cola Downey, CA, 20 electric trucks and chargers |

|

Watt EV |

Sacramento |

CA |

Planned |

18 |

Sacramento County WattEV Innovation Freight Terminal (SWIFT) – megawatt chargers |

|

Watt EV |

Bakersfield |

CA |

Under Construction |

16 |

Bakersfield truck stop – 360 kW chargers |

|

Watt EV |

Bakersfield |

CA |

Under Construction |

15 |

Bakersfield truck stop – 240 kW chargers |

|

UPS |

Compton |

CA |

Operational |

15 |

UPS Compton, CA – last mile delivery vehicles |

|

Rochester RTS |

Rochester |

NY |

Operational |

10 |

Rochester RTS first 10 electric buses |

|

OK Produce |

Fresno |

CA |

Operational |

9 |

OK Produce Fresno – eCascadia charging |

|

Oahu Transit Services |

Honolulu |

HI |

Operational |

9 |

Oahu Transit Services bus depot |

|

King County |

Seattle |

WA |

Operational |

9 |

King County South Base electric bus chargers |

|

Axis Electrified |

Newark |

NJ |

Planned |

8 |

Port of Newark electric truck DCFC charging lot |

|

Daimler Trucks North America |

Portland |

OR |

Operational |

8 |

PGE Electric Island, Portland, OR |

|

Anheuser-Bush |

Los Angeles |

CA |

Operational |

8 |

Anheuser-Bush – Pomona Site (8 Class 8 Day Cab (8TT) trucks) |

|

Penske |

Ontario |

CA |

Operational |

8 |

Penske, electric truck chargers, Ontario, California |

|

San Diego Metropolitan Transit System |

San Diego |

CA |

Operational |

6 |

San Diego MTS Imperial Avenue Division |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Coachella |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Coachella |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Ontario |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Ontario |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Barstow |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Barstow |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Arvin |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Arvin |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Lebec |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Lebec |

|

Travel Centers of America |

Buttonwillow |

CA |

Planned |

6 |

EV Oasis South – microgrid-enabled, electric charging equipment for heavy-duty trucks – Buttonwillow |

|

Titan Freight Systems |

Portland |

OR |

Operational |

6 |

TITAN Freight Systems Portland, Oregon eCascadia charging site |

|

Anheuser-Bush |

Los Angeles |

CA |

Operational |

5 |

Anheuser-Bush – Sylmar Site (5 Class 8 Day Cab (8TT) trucks) |

|

US Foods |

La Mirada |

CA |

Operational |

5 |

US Foods, La Mirida, CA, Freightliner charging site |

Methods

LCFS & 30C Tax Credit

The estimated Low Carbon Fuel Standard value is based on modeling from Dean Taylor Consulting for California, Oregon, and Washington and does not include capacity credits. It uses a 2023 – 2032 EV adoption trajectory for those three states that meets President Biden’s light-duty vehicle goal of 50 percent zero-emission vehicle sales share by 2030 (which is lower than the trajectory modeled in the EPA’s proposed vehicle emission standards), an MDHD EV adoption curve modeled on the EPA’s proposed emissions regulations for medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicles, and modeling from Atlas’s INSITE tool of MWh demanded by MDHD vehicles.

The estimated 30C tax credit value is based on modeling from Atlas Public Policy, based on EV adoption consistent with a) 50 percent of light-duty vehicle sales being battery electric by 2030 (in line with President Biden’s goal), and b) medium- and heavy-duty battery electric vehicle adoption consistent with the EPA’s proposed light-duty and medium-duty vehicle and heavy-duty vehicle regulation. Atlas assumes that 1) all qualifying projects receive the tax credit and, 2) on average, qualifying projects will receive tax credits worth 18 percent of covered costs. Atlas used the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s recent guidance in its calculation, which specified that the Treasury will classify a census tract as rural if at least 10 percent of blocks are classified as non-urban.

Private Funding

Private funding in this analysis includes public commitments from private companies to invest in EV charging infrastructure dedicated for MDHD vehicles. This analysis conservatively excludes funding commitments that could go to light-duty vehicles, if it is not clear how much is expected to go to MDHD vehicles. This also includes estimated charging infrastructure investment associated with commitments from fleets to deploy electric vehicles. Investment is calculated based on the estimated charging infrastructure needed to support the number of EVs committed by fleets.

Alternative Fuels Data Center (AFDC)

AFDC identifies charging sites as capable of supporting MDHD vehicles based on whether MDHD vehicles could physically fit in the charging parking spaces (e.g., the spots are pull-through spots). Importantly, AFDC only collects this data for sites where it does not have access to a web application programming interface (API). To try to fill in some of this gap, Atlas identified certain site types that generally provide services to MDHD vehicles, such as truck stops, and added those sites to the count of sites that are well-suited to support MDHD charging. These chargers are not included in the investment total ($30 billion), but are simply discussed in the report.

Public Funding

This analysis includes the following:

· Public funding awarded directly to MDHD charging

· For public funding awarded to MDHD vehicles, Atlas includes the estimated investment in charging infrastructure needed to support the funded vehicles.

Funding that has not yet been awarded but that might go toward MDHD charging is not included in this analysis, but is included in Table 4 in Appendix A.

Utility Filings

This analysis includes approved investor-owned utility funding for which MDHD charging is eligible. Therefore, some of the utility funding included will likely not go toward MDHD charging. However, the analysis conservatively only includes the specific sub-programs for which MDHD charging is eligible. For example, if a $1 million program is approved that includes a residential sub-program and an MDHD sub-program, only the funding associated with the MDHD sub-program is included. This analysis also conservatively only includes funding directly associated with charging infrastructure investment. In other words, administrative budgets or education budgets are not included.

Avoiding Double Counting

Investment associated with deployed private fleets in California is excluded from the private funding count because it is assumed that all MDHD vehicles deployed in California received funding from HVIP, which is already counted under public funding. This is likely a very conservative assumption since many private fleets receiving HVIP funding will also contribute their own funding. Similarly, investment associated with deployed transit and school bus fleets is excluded from the public funding count because it is assumed that these fleets used funds from public programs that are already counted under that category. Similarly, this is likely a very conservative assumption since many of these fleets likely contributed their own funds as well. Finally, to be conservative, investment associated with specific fleets is reduced to 70 percent, to avoid double counting public and/or utility funding the fleets use.

1 This includes investment announcements, investment that has been made available through funding programs, and investment associated with EV fleets in various stages of development and operation.

2 An upcoming publicly-available dashboard will allow users to explore the underlying data for this analysis.

3 Please see the Methods section for details on assumptions and calculations Atlas made to estimate of 26 U.S. Code § 30C tax credit payments.

4 Atlas used Environmental Defense Fund’s Electric Fleet Deployment & Commitment List to get data on fleet deployments and plans: EDF-Electric Fleet Deployment & Commitment List – Google Sheets. See the Methods section for more details, including how the analysis accounted for potential double counting between private and public investment (for example, private fleets that use public funding).

5 This column lists the status of the furthest along charging site identified. The status listed does not necessarily apply to the full investment amount listed.

6 In order to avoid double counting, not all of these fleet investments are included in the total reported. See the Methods section for more details.

7 Sites are considered “well-suited” if they have been identified by AFDC as MDHD charging sites or they are located at site types that generally provide services to MDHD vehicles, such as truck stops. See the Methods section for more details about how sites are determined to be well-suited for MDHD charging from AFDC data.

8 Duke Energy (Florida, North Carolina, and Indiana), Xcel Energy (Minnesota and Colorado), DTE Energy, Ameren Illinois, Eversource Massachusetts, NV Energy, Dominion Energy Virginia, PNM, Portland General Electric, Potomac Electric Power Company, Hawaiian Electric Company and Consolidated Edison